Effective science-to-public communication: How it works or can work.

Do you remember a really good piece by scientists published in a newspaper, on social media or broadcasting? Not so easy, right. But there are a few examples, and once you know what needs to be considered for effective science-to-public communication you realize: It is not as obvious as it seems, to translate research results into text or visuals or to create an exciting storyline. How it can work?

Let’s ask incoming fellow Sarah Klosterkamp (University of Bonn) who joined the research platform “The Challenge of Urban Futures” at University of Vienna in December 2022. Sarah is a geographer and journalist working on topics such as …

Kerstin, James and Yvonne, researchers at the working group “Urban Studies” at University of Vienna, hosted Sarah and discussed with her the key essentials.

Interview

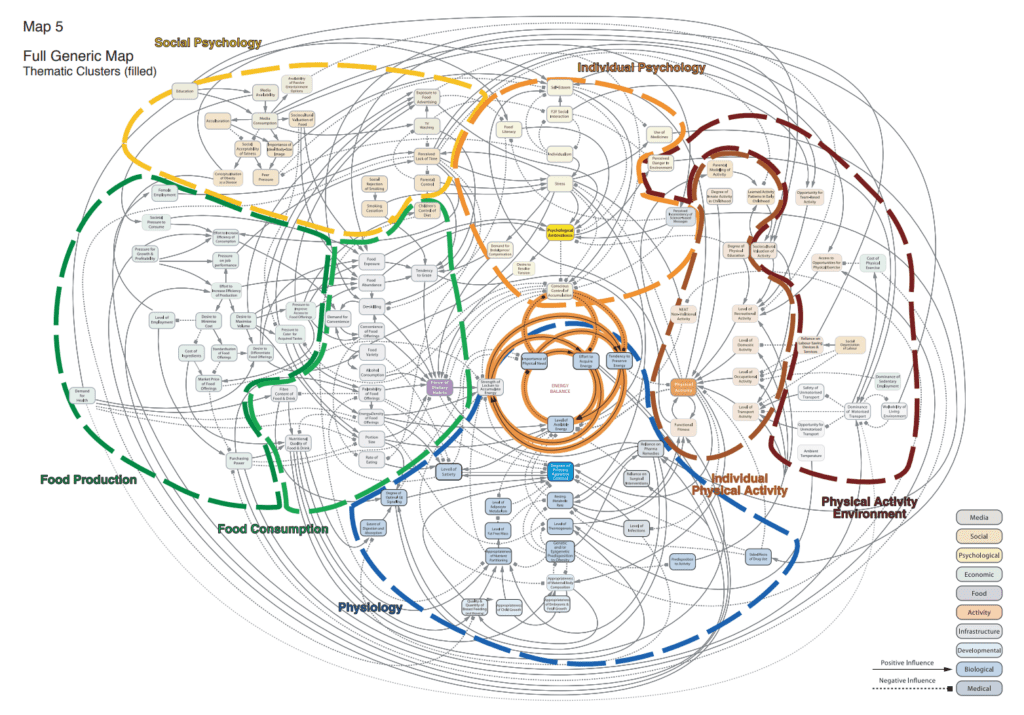

James: I brought a piece which is called “The UK Obesity System Atlas”, or as many researchers have deemed it, a ‘Horrendogram’. It shows how a diverse range of interconnected sectors of society, from psychology, to food production, the economy and urban infrastructure, contribute to obesity in the UK. However, as it is clear that the complexity of the diagram is overwhelming, I wonder how such poorly readable illustrations hinder the ability of journalists to communicate important issues to the public, and what type of far reaching consequences such can have throughout society?

Sarah: Thank you for this question. The diagram is a great example for problems, which can occur if we, as scholars, are deeply involved in our research topics. Presenting such results to colleagues, working on the same topic, is great. But for public outreach, it is just too rich – and yes, as you said, perhaps even quite overwhelming. On the other hand, I don’t think, that journalists are prevented or hindered to work on topics like this. If the topic is important, they will continue to work on it either way – but they may ask other scholars for an interview, who perhaps, a) propose more clearly with material easy to grasp and b) might already be on their radar or got recommended as a good sparring partner. Of course, something gets lost. Presenting a topic to your research community or via public outreach follows other criteria and depth. But I would say, it is definitely worth it to pay attention to these dynamics and be prepared.

Yvonne: During interviews with journalists, I realize their interest in short, plausible, easy-to-digest answers to their questions. But in research, easy answers are rare and most of the time researchers tend to explain the context and conditions before they present actual results. Is there any middle-way to prevent simplification while avoiding overly complex answers? Do you have any recommendations what to keep in mind as researcher?

Sarah:

As geographers, we all work on much important topics, such as the effects of the current climate crisis, desirable urban futures and social and economic inequalities, which lead to further exclusion. All of these are much troubling for society these days and solutions need to be found. To make sure, that you get heard with these topics, you need to make sure, that people understand your argument. Being short and much precise helps in this regard. Perhaps having in mind, that this is the only way to be heard and understood, you need to train this type of research presentation. If you are good (or getting better in this), you can present complicated topics even with carrying on as much detail as possible. So, I would say: Preparation is key – my personal recommendation is “a four-step procedure”. I prepare every media output (and the way I unfold it) by following four question. If you are following this lead, you might be good prepared for a standard 3-minutes media interview:

- The first one is: “Who is the audience?” Visualize it and then adapt your language!

- Second: You need some good punchlines: What is your argument? Be short and precise!

- Third: Why is your topic important? Provide an intellectual argument, which draws on the bigger picture.

- And lastly: What is the solution? Provide a take home message for your audience which connects the three aforementioned items.

The more often you put yourself into situations like this, the better you get. Some universities offer assistance herewith. Perhaps, reaching out to yours and asking for support, might be also a good idea. Training and assistance are key!

Kerstin: Time is often a constraint in researchers’ daily life. Science-to-public communication is often an additional task that consumes even more time resources, although it is of course of high importance in order to communicate our research more broadly. Do you have any recommendations how to keep the additional efforts small? Or is there a way of effective planning?

Sarah: That’s a challenging one. I agree, the time issue is something, we all have to deal with. When talking with colleagues or during workshops I attended to, this is the number one question of why most academics step back from this. But I think, especially within these days, since fake news are a thing, a way out of the polycrisis highly depends on expert knowledge. So, getting out there with the work, we, as geographers, are doing, is more important than ever. Also: It is a learning setting – engaging with journalists and other colleagues when working on these outlets is a great way to even expand your own insights. I strongly believe, that it doesn’t take much time to do a solid public engagement, if you perhaps just do the bare minimum, by being present on social media and share the work you and your colleagues are doing there, already helps a lot in terms of visibility – for the themes, but also as presenting yourself as an expert and/or actively working on these topics. So, in the end, it might be something in between: a small additional effort, sure, but with a good planning, it shouldn’t have to be an extra add-on to your weekly working hours.

Sarah’s take home messages:

….when working with media outlets

- Media outlets work differently (than e.g. universities/research institutes), their effort can be in line to our own efforts, but it can also contradict them

- Look out for people of which you already like what they are doing / the way they are depicting the topic you care about/work on/have your expertise

….when working with students

- Collaborations with policemen can be questioned. What is our role here? What is theirs?

- A good example: Student Academy: “No piece for justice”. This collaboration of three different origins (police/research/theater) were for everyone involved truly inspirational & helped diversifying different perspectives to the topics at stake + pushed public interest (big coverage within German local newspapers)

….when communicating on social media

- Witnessing how others get into shitstorms, doesn’t feel good

- This leads (perhaps) to the need to reconsider what and where to share what I/we do.

- Allyship is important! Who do you want to work with and what vulnerabilities do they carry on? Are they on social media as well, why/why not? Figuring out a good way to do so, might be a good step forward!

Innovation ahead: USL’s favorite examples for innovative research-to-science-communication

- How is (super)diversity changing how we belong? https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=xYXrwcW-1Vc [last access: 21.02.2023]

- Example 2 + link

- Example 3 + link

References:

Vandenbroek, P., Goossensm J., Clemens, M. 2007. UK Obesity Atlas. UK Government Foresight Office. 1-46.